Goal setting is more than just declaring intentions; it’s an imaginative, continuous process that shapes our journey toward success.

Reflecting on my 20-year rowing career and the inspiration drawn from the “Oarsome Foursome” during the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, I’ve realised the importance of blending aspiration with practicality.

Having been coached by James Tomkins in 1992, one of the “Oarsome Foursome” members, I learned firsthand that these athletes, despite seeming like ordinary individuals, achieved extraordinary feats. This realisation brought both inspiration and a reality check—success is possible for anyone willing to pursue it with rigour and resilience.

Goal Setting and 6 Hats Thinking

By applying Edward de Bono’s thinking hats model, particularly the yellow hat (optimism), black hat (critical risks), and white hat (factual thinking), I’ve navigated through my own blend of optimism and self-doubt. This method has helped me to evaluate my capabilities realistically and to reinforce my aspirations with tangible evidence gathered over time.

Persistence and closing the gaps

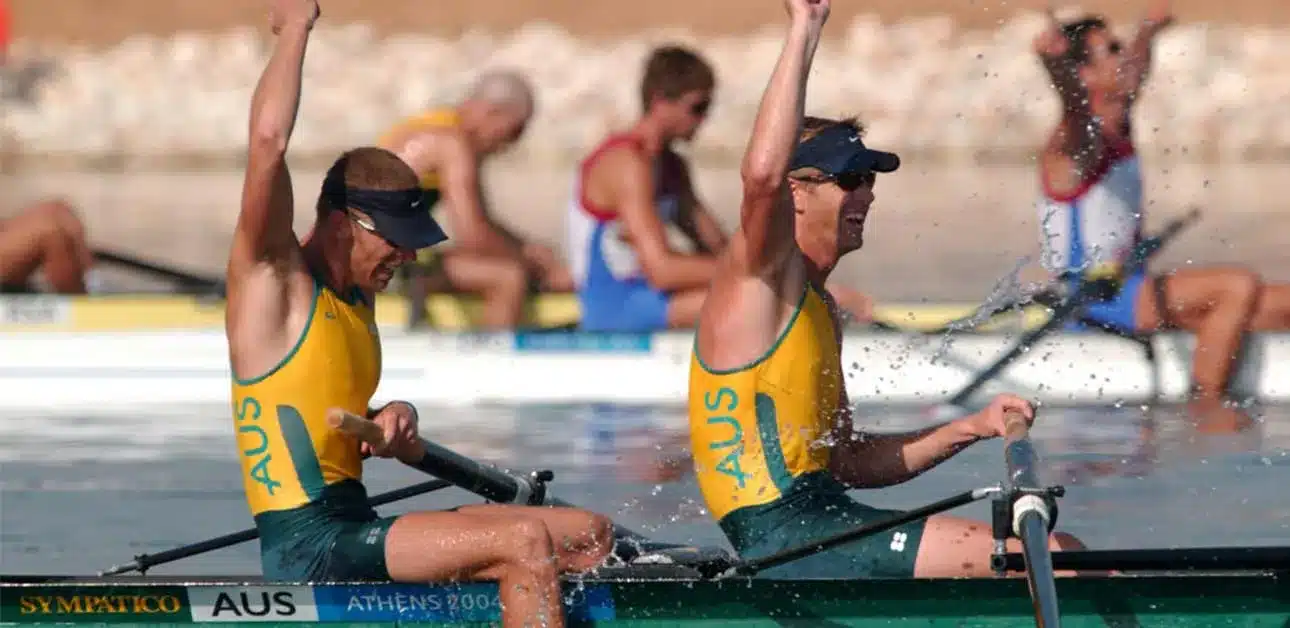

The story of the South African rowers, Donovan Cech and Ramon di Clemente, is a prime example of how sustained effort and realistic assessment can bridge the gap from ordinary to extraordinary. Their journey from novices to Olympic medalists in just three years illustrates the power of incremental achievements and persistent vision.

However, effective goal setting isn’t a one-time event—it’s an evolving dialogue with oneself. Continuous engagement with our goals is essential. We must adapt and respond to challenges, gathering data and adjusting our strategies accordingly. This process is not static; it’s dynamic, requiring constant interaction with our ambitions.

In the same way rowers and crew adjust their course in response to varying wind conditions, we must remain adaptable in our pursuits of our goals. Flexibility and intentionality are crucial as we navigate toward our goals, maintaining a balance between optimism and realism.

Ambitious and bold goals

Australian sailor Jessica Watson set a goal to become the youngest person to sail nonstop and unassisted around the world. At 16, she meticulously planned her journey, trained, and faced many challenges at sea. In 2010, she successfully completed her circumnavigation, demonstrating the power of clear, ambitious goals.

In practical terms, balancing ambition, adjustments, reality checks all means when setbacks occur, it’s crucial to adapt rather than abandon our efforts, or emotional connection to what we aspire. Like steering a boat against the wind, we must adjust our methods while staying focused on our final destination.

Goal setting and adaptability

From early in his career, New Zealand rower Mahe Drysdale, set the lofty goal of winning Olympic gold and I suspect it was either prior to 2004 in the men’s four or after when he really started to believe. I am sure his ultimate aim of becoming an olympic champion guided all his training, nutritional plans, and race strategies.

I imagine Drysdale and his coach Dick Tonks broke down this aspiration into specific training objectives, and I am sure these related to volume of training, repeatable race pace efforts, some simple technical focuses and an approach around small boat pods of athletes and crew for competitive and camaraderie. Clearly the aim would have included enhancing his rowing technique under pressure, building endurance, and increasing strength, and ultimately create sustainable boat speed that could challenge and overcome the best single scullers in the world.

His journey was fraught with challenges, including a serious back injury during his career and specifically gastrointestinal issues during the 2008 Beijing I assume this challenge as the Olympics in 08 had an impact on his performance. Yet, he demonstrated immense resilience by recovering and continuing to compete and win a medal.

Beyond his physical training, Drysdale developed some amazing psychological skills, as I think his was one of the best examples of toughness in International races with a never give up attitude and capacity to keep digging in to generate boat speed. With his challenges around his back issues and management I am aware he incorporated more bike riding to compensate for his volume and it was something he and his coach adapted to help him stay dominant in his preparation and competitions.

His constant drive towards his goal and the structure of the approach with his coach and the NZ squad, combined with any adjustments he made to enable himself to press forward and execute on his goals. Winning the Olympic gold medal in the single sculls at the 2012 London Olympics and defending his title at the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics is a remarkable achievement and I think a great example of goal setting, and processes around imagining, adapting and delivering on goals.

Benchmarking

This mindset around goal setting and adaptability encourages us to embrace change as a natural part of any success journey, rather than resisting it out of fear or discomfort. By setting tangible benchmarks and allowing room for flexibility, we create a robust framework for achieving our aspirations.

Oarsome Foursome Benchmarking

In 1996 my first insights into benchmarking came after goal setting meetings with the Oarsome Foursome. I remember a meeting at Mike McKay’s place in late December 1995 or early January 1996, which was about clarifying our goals, defining success and identifying drivers and inhibitors of that success. Soon after in training I had an experience that created a lasting impact. The guys said in 1992 they had a clear benchmark related to paddling speed in the four, rate 18-20 strokes per minute at 4.2m/s.

This benchmark was about consistency and rhythm and ideally heart rates as an indicator relative to the boat speed guided training and created confidence. Initially we had to work hard to get on this speed and during that domestic preparation and competition it helped us gain selection. We then headed overseas and had our first race in Germany, and found we were smashed by the Italians and oher off the start along with not being overly competitive later in the races. Quickly this became a serious conversation about our goals and revising the benchmark. Mike was adamant we need to push the standards forward and this was one of our indicators so a new benchmark was set of 4.4m/s and with further work and prep we found ourselves coming 2nd in Lucerne only 0.6sec behind the Italians and this was a huge boost in confidence.

We push further with the benchmark from that moment identifying that 4.5m/s was the next level we need to work towards. I was sitting in the bow seat and had the speed coach (device) with the old arm and sensor in the water off the side of the boat and I would watch it like a hawk and provide feedback. In July at the Olympics we succeeded in winning Gold and the margin ended up being 0.6sec and from that experience I became a huge believer in benchmarking and how it helps drive performance based on goal setting.

Final note here is I am not suggesting there is not more to the process rather the crew and athlete goal discussions and finding agreement drove learning and performance, and benchmarking and being adaptable enable progress forward with our ultimate aim of making the boat faster, and faster under competitive conditions.

My personal takeaways from exploring goal setting deeply have reaffirmed the importance of being proactive and engaged in every step toward achieving my ambitions. It’s about fostering a ‘muscle’ of hope through cycles of aspiration, reflection, and critical thinking, which strengthens our belief in our capabilities.

To anyone navigating their own path toward goals—whether in sports, business, or personal development—remember: innovate, adapt, and persevere. Let’s keep imagining better outcomes and be ready to embrace the innovations that could redefine our fields and inspire future generations.